Mrs. Clay Survives Indian War of 1877

Taken from the Meadows Eagle, 1911:

Graphic Recital of the Experience of Mrs. Thomas Clay during the Indian War of 1877.

It is rare that one has the opportunity of speaking to one of the pioneers of the country who has passed through one of the historic massacres of the state and hears the story direct from the lips of one who has suffered much at the hands of the blood thirsty redskins.

Mrs. Katherine Clay, a fragile little brown-eyed woman about 65 years old, now living at Meadows, Idaho, had the terrible experience of seeing her husband and two friends murdered before her eyes by the Indians, and her four small children torn from her when she was carried away at this time, walking almost constantly for 24 hours, carrying a babe, only to meet the Indians, from whom she had been fleeing all this time and then compelled to walk for another 6 hours to reach a haven of safety, was enough to have killed or driven insane a less courageous and gritty woman.

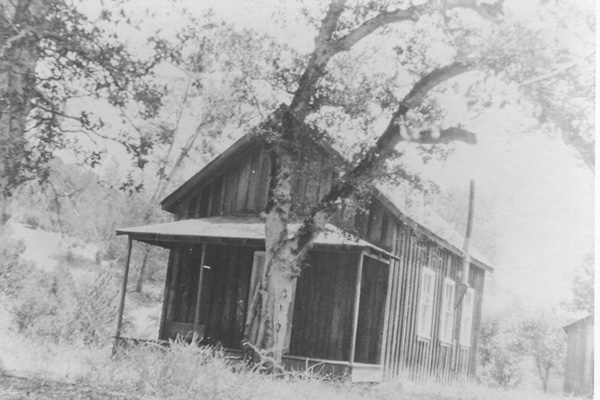

[Elizabeth] Katherine Kline came over from Germany a mere slip of a girl with relatives, coming “round the Horn,” and going in the spirit of adventure to the Warren Diggins in North Idaho. Here she married Mr. Osborn, and after a short time spent at Warrens, they sold out their interests and went to the Salmon River Country. It was while living here on June 13, 1877 that Mrs. Osborn passed through the most horrible experience of her life. They were living at French Bar, what is now the town of Whitebird. The men of the family, Mrs. Clay says, were out helping the neighbors get in their hay when a messenger rode up and shouted that four men had been reported killed by the Indians on Slate Creek, not far away. The men were sent for, and Mr. Osborn and his brother-in-law, Harry Mason, commenced at once to arrange to get the people of the surrounding country together at the cabin of Old Man Baker, whose place was so built that it could be better fortified than any other cabin in the vicinity.

Mrs. Clay, then Mrs. Osborn, with her four children and Mrs. Walch, her neighbor, with two children, started with three men, Mr. Osborn, Mr. Mason and a man known as Big George for the Baker cabin. Having only three horses it was necessary that the children ride, and Mrs. Walch not being well, rode also, leaving Mrs. Osborn and the three men to walk.

Nervous, full of excitement, Mrs. Osborn darted ahead of the men all the way. Arriving at a creek so deep that they had to all use the horses to ford, Mrs. Osborn crossed first, and just as she came to the fence surrounding the Baker cabin, she spied the Indians. They at once commenced to fire, aiming high up. She sank to the ground and called to the rest of the party. Her husband reaching her, she pulled him down, taking the youngest child in her arms saying: “We might as well die together,” believing it was their last moment on earth. In telling the story, Mrs. Osborn said, “The bullets were so thick that they seemed like snow.” Dropping down as they did in the midst of the willows surrounding the Baker place. The Indians evidently lost sight of the party for they soon passed on to the Baker cabin.

After waiting a time the party cautiously crept up the creek to a shallow spot where they recrossed, this time on foot-the water coming to the waists of the women. It was necessary for the men to make six trips across the creek before they got the women and children all across. They had but one gun with them, and at this time but two cartridges left. One of the stray shots from the Indian’s rifles had hit the little finger of Big George, who suffered intense pain. The little party had left home at 2 o’clock the next morning. They held a council, and concluded the safest thing to do was to go down to Lewiston in a boat. At the store kept by Harry Mason, about a mile from the home of the Osbornes, which was only a short distance from the present town of Grangeville [sic*], they knew they could get some boats. Arriving at the store they found that the Indians had been there and had stolen all of the whiskey and supplies. They started up to the Osborn home to get some supplies to take with them, and just as they reached the door of the cabin, Mrs. Osborn called out, “Here they come!” She being behind the party all this time, caught sight of a band of 18 braves winding down the hill, rods away.

*[The Mason Store was near the mouth of Whitebird Creek, not for from present-day Whitebird.]

At the alarm given by Mrs. Osborn the party at once hurried into the cabin, the women and children crawling under the bed. No sooner did the men bar the door than the Indians were upon them, and firing through the window. The first shot went directly through the heart of Mr. Osborn, who fell over dead not two feet from his wife. Other shots stunned both Mason and big George who was with the party. The Indians then started to burn the house, setting fire to one corner.

The women debated what they should do when they saw the fire, having apparently only two alternatives, that of being burned to death or tortured to death. Just then Big George, who hard been stunned by the shot which he had received, aroused himself and jumped on the bed to protect the defenseless women just as the Indians broke open the door. His brains were instantly blown out, and as Harry Mason raised his head, he met the same fate. The two women and their six helpless children were thus left to the mercy of the drink-crazed redskins.

In telling of the horrible events of this awful day, Mrs. Osborn stated that no a child whimpered, even when the shots were fired. In spite of their long journey, through every obstacle, and even going without food, they were absolutely quiet.

When the door was burst open, Chief Whitebird entered and assured the women that he intended to spare the women and children. In spite of his protests, they were treated shamefully, the chief seeming to have no influence over his braves. “They started to ransack the house,” says Mrs. Osborn, “and I was so nervous over all I had gone through that I was pretty sassy, I guess, and Whitebird Said, “You keep still; if you don’t, I can’t protect you.”

The chief finally succeeded in getting the women and children out of the house, and they started for the home of Uncle John Woods, 12 miles way. On the way, they met Mr. Shoemaker, who had originally started with them in their flight from the Indians, but whom they had dropped behind at some point. Putting the youngest child of Mrs. Osborn on his back, he started ahead. He arrived first at the Woods home, where both were known, and was so stunned from the happenings of the day that he could not tell anything, and taking the little 2-year-old child on her lap, Mrs. Woods learned from it the full tragedy. “Pap shot dead, uncle dead, Indians shoot. Momma coming.”

Mrs. Wood made out enough of the story to guess what had happened and her husband at once sent out a friendly Indian with the one horse they had, to meet the party. Mrs. Osborn says that when she saw that friendly Indian, whom she had known before, coming on the Wood’s horse, she fainted away. During all the horrors of the 24 hours she had kept her senses, but now that aid was in sight, she fainted.

The two families remained at the Woods home for six weeks when they went again to Warren’s Diggings. Here Mrs. Osborn supported herself and children by taking in washing, the only thing she was able to do, and at the time she weighed only 84 pounds. About year and a half later she married Mr. Clay who died 19 years ago.

Mrs. Clay has lived to rear six of her eight children, to give them all a good education and to now enjoy her old age among her grandchildren. The terrible tragedy of the awful 13th of June, 1877, while still fresh in memory in its minutest detail, is now more like a horrible drama which she witnessed, rather than an actual happening of real life in which she played one of the star parts. Her home for some years has been at Meadows. She says that during the last six years she has lost track of Mrs. Walch, her companion of the tragedy.

One Response to “Mrs. Clay Survives Indian War of 1877”

My great great grandmother was the Mrs. Walch mentioned in the story above. Her actual name is Helen Julia Mason Walsh and her account of the tragedy can be found in the University of Washington Library. Was there any additional information in this article that is not included here?

Leave your feedback: